Self-Learning and Braille: How Educational Technologies Can Help

The written language scripts we learn are key to observing and recording our world. Learning Braille, then, is a valuable bridge to comprehending the world for people with visual impairments - and as with any other form of learning, it is often helped greatly by a guide, a teacher, a companion. But the role of such a guide and the form they may take in someone’s educational journey is changing with our world, and education for visually impaired children must reflect those changes.

Self-learning, also called self-directed or self-regulated learning, is now commonly recognized as an important approach to getting learners invested in their own education. It’s a means to make sense of their world in ways that make sense to them, through their own senses. This doesn’t mean that the role of an educational guide, a kind of teacher, is made redundant - but it does evolve. The educator needs to interact with the learner in a more engaging manner, providing feedback based on the needs of the learner, rather than the presumptions of the educator.

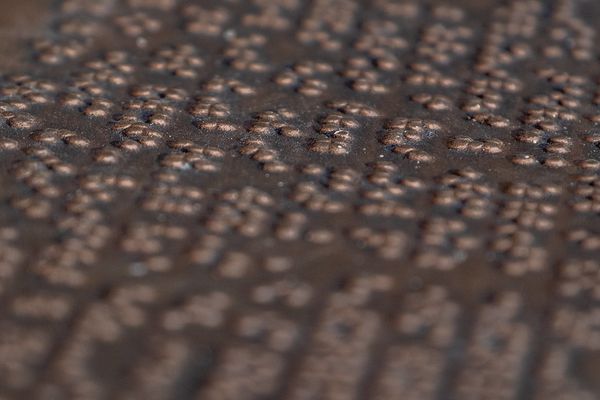

With the low number of qualified teachers for visually impaired children, especially in India, and the typical micro-engagement (often at a one-on-one level) between the educational guide and the learner in Braille education, it’s evident why we need to rethink Braille learning. It is here that educational technology - such as Thinkerbell Labs’ Annie - can fold interactivity, gamification and feedback in support of self-learning.

Choosing How to Learn

The key element to self-learning is choice: enabling students to choose what they’d like to learn, when, and how - in short, the student largely directs their own learning. This is also intended to encourage students’ adaptability to different pedagogies and modes of learning. By trusting that learners know their own strengths and how to apply these to their education, they have the space to cultivate their own educational strategies and skills. Simultaneously, self-learning is also a chance for students to learn new cognitive skills - how to select, combine, and coordinate strategies to help themselves learn better. There might be certain aspects of what they learn that they choose to engage with deeply, others more casually - these shifts are to be entrusted to the learner. This represents a “paradigm shift in how students conceive of and approach their learning, with a major reorientation in students' assumptions and expectations about teaching and learning.”

Still, the classroom as we know it has some major strengths: it offers a way to learn with students at the same age and with similar skill sets, encourages socialization, and has the consistent support of the teacher - an experienced educational guide. In fact, such learning environments can facilitate the development of self-learning skills too, applicable both in and outside the classroom.

So how can we ensure learners have access to the benefits of a classroom environment when they’re learning on their own? With the advent of technology- and computer-enhanced learning, it seems we might have an answer. Several studies have found that the use of technological tools - from computer laboratories, to incorporating students' everyday phone use into their education, to developing educational technologies specifically for students’ needs - motivates students to engage with academics to positive results. Such students are keen to participate in self-learning activities, and take greater responsibility for their own learning.

We have observed - and enabled - these shifts in learning with Annie, our Braille self-learning innovation. While most learners use Annie in classroom-like Annie Smart Classes guided by their teachers, they also have the opportunity to pick which lessons they want to learn from on a given day, which games to play, what to revise and what new skill (reading, writing, and typing in Braille) they want to practice. They are free to repeat lessons, diving into them at their preferred pace. There is no push to keep progressing, but they have the freedom to explore learning materials independently of their peers. Still, they have their teacher to guide their learning when necessary, and peers to share what they’ve learnt. Across Annie Smart Classes, we’ve observed this approach dramatically improve students’ performance in Braille skills.

How Do We Learn?

Braille, unlike most other language scripts, is tactile. It’s closer to the reader - the learner - than others. This makes Braille well-suited to the cycle of self-learning, involving (1) forethought, (2) performance or volitional control and (3) self-reflection, where the learner engages directly with the learning material in Braille in both thought and action, and where a teacher may not be able to provide constant, granular feedback without the risk of intruding on the self-learning process - a level of interaction that’s unrealistic in regular classroom environments.

Learning Braille, then, can be made more effective and exciting through multimodal learning - engaging both auditory and kinaesthetic senses to help children with visual impairments form their own understanding of the visual world sighted people are used to. After all, the learning process - like any form of communication - depends on a number of ways to make sense of the world, motivated by the interests of the learner, their perceptual and cognitive strengths, and their environments.

Blending self-learning and multimodal mechanisms allows students to feel more comfortable with their preferred learning style and perform better, learning concepts through text and audio, real-world examples, and interactive lessons. From in-class texts, to homework and assignments, to feedback - everything can be multimodal.

Technology and computer-enabled learning is particularly useful in presenting multiple ways to learn, both in what children can learn and how. Annie’s mix of Braille cells, keyboard, Brailler and audio output, for example, provides learners with a variety of ways to read, write and type in Braille, as well as match auditory instructions to the Braille script. With these multimodal pedagogies that allow students to question their long-held beliefs or knowledge, they can learn to change and challenge their own learning. This improves students’ understanding and retention of what they’ve learnt, their confidence in class, their interest and enjoyment of learning, and ultimately, a lasting commitment to their education.

How Do We Learn Better?

For the self-learner figuring out the many (multimodal) methods of learning out there, three things are key to a deep learning experience: interactivity, feedback, and gamification. Per a classic study describing “The Learning Pyramid,” using learnt skills and knowledge immediately, and participating in discussion groups pegs retention rates at 90% and 75% respectively. It’s evident that deeply interactive learning, when coupled with quality gamified lessons, and regular and comprehensive feedback, facilitates deep learning by actively engaging the learner in their own education.

For technology-enabled interactivity, it’s important for learning materials and the interactive element to be based on the skills of the learner, rather than the capabilities of the technology. This interaction has three actions:

- The device presents the interactive element to the learner (computer initiation),

- Learner presses the button or on the Braille element (learner response),

- Presentation of new information to learner (computer feedback).

Done right, this interactivity balances the independence of the learner’s response with its relevance to the learning material. The feedback, meanwhile, uses the direct response to explain the concepts that the student is learning.

If this sounds drily mechanical, it’s because it can be. That’s why gamification is so useful - by using game thinking and design that utilize innovative rewards such as high scores, as well as the sheer joy of playing, interactive lessons can be remarkably motivational learning tools. These games are aligned with learning objectives, but more than traditionally one-sided lessons, take the learners’ motivations and attitudes to learning more seriously. They are engaging and rich in multimodal and multimedia elements. In the gamification of education, learners have the opportunity to repeatedly try multiple paths to the gamified lesson’s objectives with scaling difficulty levels - such as in Braille, learning to read certain letters of the alphabet at increasing speeds. These ‘games’ are also realistic about what can be achieved through such gamification - they aren’t meant to substitute for example, creative thinking.

We’ve recognized the strengths of interactivity, in all its forms, in students learning with Annie. The interactive lessons - that gently provide feedback at key points of the lessons; the games that help children hone their performance and speed in using Braille as well as compare their scores with their peers on a leaderboard for that extra competitive nudge; the Helios suite that enables feedback from teachers by tracking student performance and helping teachers prepare their future lessons accordingly.

Adapting to self-learning

Bringing self-learning to the way children with visual impairments learn Braille - including in the classroom - is not a straightforward task. Learning materials need to be reworked, pedagogies rethought, classrooms redesigned. It’s important to keep in mind that self-learning involves a shift in thinking for both learner and educator, and the particular strengths of the classroom - such as learning with friends, and including them in social circles - is not overridden by self-learning. The good news is these changes can be adapted to more easily with the help of technology.

With Annie, we’ve learnt of both the power and complexities of technology-enabled self-learning. We’ve found students grow more excited and invested in Braille, without needing to separate the enjoyment of learning from the educational environment. Annie let them pick up the lessons they were interested in, and they’ve raced ahead of their existing knowledge. At the same time, by recognizing the need for teachers to manage the overall learning environment and help their students navigate these new modes of learning, we’ve stepped back from what self-learning cannot achieve. With touch, sound, and - we think - quite a lot of fun, Braille self-learning can be a wonderful new way for visually impaired children to learn about the world.