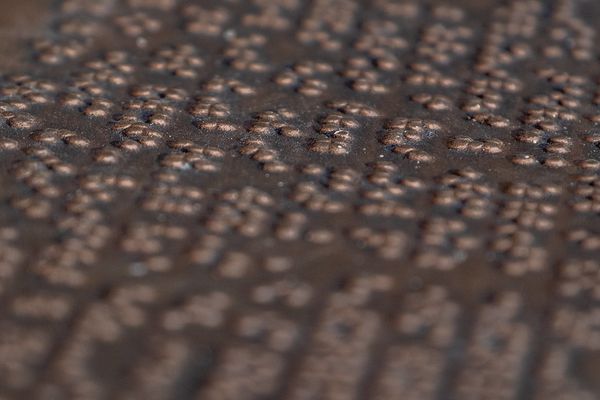

How Unified English Braille (UEB) Simplifies Braille

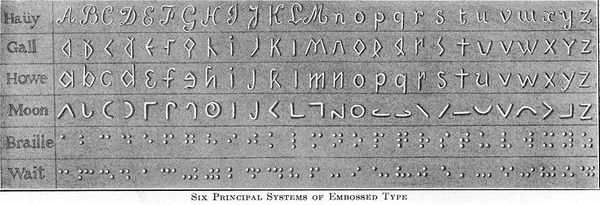

Through Braille’s long and varied history, many countries designed their own Braille codes to meet the needs of their languages and cultures. It’s no surprise, then, that this has sometimes meant inconsistencies in the script across the world. The uneven spread of Braille in Europe and North America, and its later introduction in Australia and other countries, has meant that these countries had each adopted different versions of English Braille.

These differences had previously made it difficult to have a standard form of English Braille. This was especially problematic when it came to crossing national barriers with technical codes and literary texts. Unified English Braille, or UEB, is the unified Braille script that’s designed to remove these barriers for good.

The History of UEB

The foundations for UEB were laid in a 1991 memo written by Braille pioneers T. V. Cranmer and Abraham Nemeth, where they recognize the eroding use of Braille across the English-speaking world. They worried that Braille would become “a secondary means of written communication among the blind, or that it [would] become obsolete altogether,” a significant factor of which was “the complexity and disarray into which the Braille system has now evolved.” This made it especially difficult for young learners, who may have to learn several different Braille codes to read and write, work on their computer, or use their calculator. A uniform Braille system aimed to take the best of the individual codes and combine the changed codes into a single standard.

In 1993, the Braille Authority of North America (BANA) and the International Council on English Braille (ICEB) began development of the uniform code - the UEB - in collaboration with major English-speaking countries. UEB produced a code which unified across the English-speaking world, as well as for literary and technical subjects. At the same time, new Braille symbols were created to keep Braille up-to-date with print usage.The UEB brings together three of the previously-existing official Braille codes: English Braille, American Edition (literary material), Nemeth Code (mathematics and scientific notation), and Computer Braille Code (computer notation).

Australia was one of the first UEB adopters, in 2005, while it took a decade or so for other countries to adopt it across the board - in 2015, RNIB (along with other major Braille producers) transferred all Braille production in the UK to UEB.

What Does (and Doesn’t) UEB Change?

UEB retains the general-purpose literary code as its base, while allowing the addition of new symbols, providing flexibility for changes as print changes, reducing the complexity of certain rules, and allowing greater accuracy in back translation.

The major changes the UEB made include:

- Spacing: Words that were written together such as "and the" were mandated to have a space between them as they do in print.

- Elimination of some contractions: Owing to translation difficulties and confusion with other symbols, "ally," "ation," "ble," "by," "com," "dd,” "into," "o'clock," and "to" were removed from UEB.

- Punctuation: A few punctuation marks, such as parentheses, were changed, while symbols for brackets, quotation marks, dashes, and others were added.

- Indicators: Bold, underline, and italics each had their own indicators in UEB.

- Math symbols: Operational symbols such as plus and equals were incorporated.

The code for letters and numbers are the same as they are in the literary code.

Why UEB?

The UEB is designed to deal with a wide range of subject matter at all levels of complexity - while not drastically changing what makes the original six-dot Braille script easy to understand. It’s systematically constructed so that as new symbols are introduced into the code, they don’t conflict with those already in the code. It’s also well-suited to technical use, so it’s amenable to computer translation either from Braille to print or from print to Braille without the inaccuracies of previous Braille systems. This is especially important because online texts see many more instances of capital letters and lowercase and numbers all mixed together. UEB makes it much easier to represent a web address, a password, or a pin number in Braille.

UEB also has major advantages in the production of Braille texts and transcriptions. More consistency, less ambiguity, and fewer exceptions to Braille rules makes texts easier to produce and makes learning Braille easier. It reduces the effort required to produce both handwritten Braille texts and transcriptions of computer-produced Braille, and allows transcribers to put more focus on the advanced aspects of Braille production rather than spending time on basic elements.

Onward with UEB

UEB is a standard code, but it’s also a system that has room to expand, so that future symbols can be easily represented in the code. Its widespread and easy adoption also makes it a boon to learners of Braille. It’s why Annie, our innovation in Braille self-learning, uses the code in the learning materials for reading, writing, and typing. With UEB’s adoption in English-speaking countries worldwide, the Braille code is achieving a consistency and coherence that makes it ideal for the needs of the visually impaired community.