The Paths to Braille Literacy

Language is a means to make sense of our world, the only way of turning thought into text and speech. The written script of a language allows us to record our thoughts and our knowledge, and share information with others in our communities who we might not be able to directly speak to. No matter the language the script is written in, then, Braille is an indispensable part of the lives of people with visual impairments. Braille is key for these persons to shape their community, asserting themselves as a group of people woven through society at large with their own ways of reading and writing it.

This journey with language starts young. For children with visual impairments, then, learning Braille is an important stepping stone to their broader education. Unfortunately, achieving Braille literacy is a complex and ill-addressed challenge. Even in countries where Braille has a long history - such as the US - Braille literacy rates are extremely low, to the point that filling this gap means pretty much starting from scratch. So what are the complexities of Braille that we need to think about?

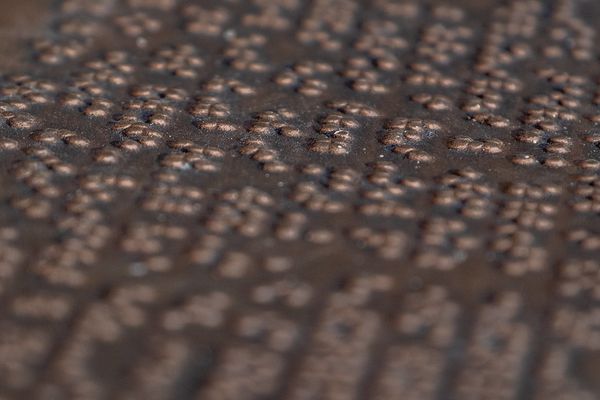

Braille’s Unique Touch

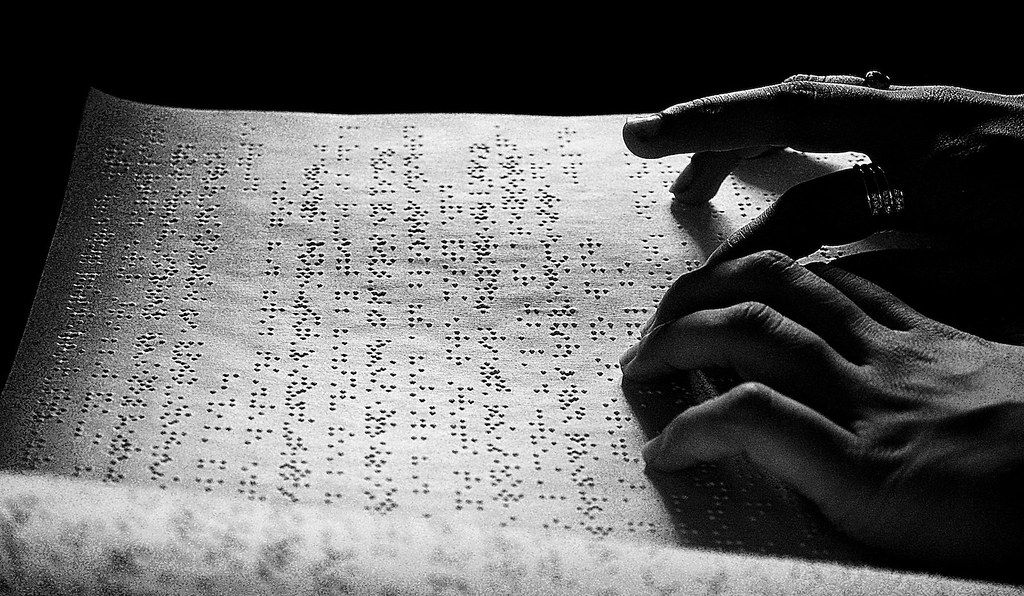

For persons with visual impairments, their sense of touch becomes the primary way to ‘sense’ the world around them. The Braille script is uniquely suited to this means of perception - it is, unlike most other language scripts, tactile. Someone with visual impairments reads Braille with their kinaesthetic sense; they can, quite literally, feel words. And with the simplicity of how the characters feel, as their precise location on paper (or even screens), and its reproducibility across languages, Braille has a lot going for it.

To those who use the Braille script in their daily lives, it goes beyond the page. Braille is not simply a method of receiving or recording knowledge or information - to many, Braille is an inseparable component of their life and identity. Braille is the symbol of visually impaired persons’ presence as an influencing social group who seeks visibility and participation. The usage of Braille is considered by the visually impaired community as assurance that society at large cares about their rights and needs. While it is true that with technological means - such as screen readers - information can reach them through other resources, turning these texts into Braille can make people with visual impairments feel that their community believes in, and seeks to preserve their particular values as a human being, exactly as visual language scripts do for others.

Of course, Braille isn't just a replacement for writing. It is easy to forget how important colours, logos, symbols and other visual signposting are to working out what something is. Being able to label clothing, food stuffs and domestic appliances around the home helps blind or partially sighted people live independently. Items such as washing machines can be almost impossible for a blind person to use unless the controls have raised or clear print markings to indicate the different settings or uses of each knob or dial. When introduced at an early age, knowing Braille even has a significant impact on chances of future employment.

This means that, quite simply, learning Braille is a matter of major importance to people with visual impairments. Teaching children the script is easier when introduced to its form and essential units - the alphabet and numbers, for a start - early in their education. Such an education in Braille even has a significant impact on children’s psychological and social development. The benefits are evident - unfortunately, the pathways to obtain these benefits, not so much. Why aren’t visually impaired children able to access these benefits like they should be able to?

Why Braille Literacy is Difficult to Achieve

Education of any form isn’t an isolated project that’s free of socioeconomic, cultural, and political forces swirling around it. This is doubly true of education for the visually impaired, with further obstacles imposed by the insufficient understanding of their specific social and policy-based needs, as well as the lack of adequate resources dedicated to these needs.

Despite its many strengths, there are some particular challenges associated with teaching and learning the Braille script. At a purely educational level, visually impaired children require close attention from their teachers in order to find their way with this unique script. Teachers often need to individually aid Braille learners with touch and a sense of the ‘space’ of the text. Braille isn’t just about the script either - just like with learning any other language script, reading instruction and basic literacy processes such as phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, comprehension, and written language must be taught from the very beginning. The assessment of a child’s learning, then, depends not only on their ability to read and write (and maybe even type) in Braille, but also their grasp of concepts they may encounter in their everyday lives, reading comprehension and their ability to make sense of the world through other means such as listening skills that compound their knowledge of Braille. This means that teachers often need to be more closely involved in the student’s learning and assessment than is the case with sighted or visual learning. There have been few changes in the way Braille has been taught for decades that seek to address these issues.

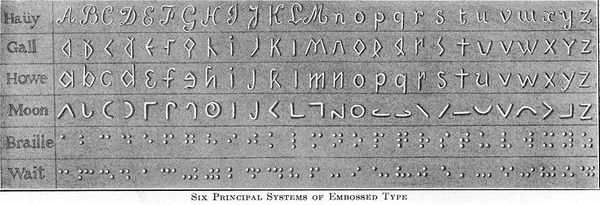

There have also been some controversies around Braille’s usefulness in recent years. On a pragmatic level, Braille texts can be difficult and expensive to produce, with limited portability. With the advent of assistive technologies, audio books, and screen readers, Braille is assumed to be out of date. However, these underestimate what Braille can mean to visually impaired children, and its adaptability to technological innovations.

There’s a cultural hesitance in elevating what would allow people with visual impairments to shape their own lives, and instead the focus is on providing a limited means of access to the sighted world. Braille users note the ease with which they can use it in classrooms and at work meetings, and its usefulness in navigating public spaces. Technologies such as refreshable Braille displays and the incorporation of Braille into everyday technologies, such as smartphones, enhance them for the use of swathes of users with visual impairments. Braille illiteracy takes away access to these freedoms.

There are also social, economic, and cultural barriers that have translated into choices of policy that have further limited the widespread teaching of Braille. Generally, people with visual impairments are a political and economic minority, with little power in the policy-making process. Hence, little attention is paid to how they can participate in society, such as by learning Braille. Decisions around the education of visually impaired people are taken by sighted people, who may not always understand their needs as well as someone belonging to that community.

This vacuum, however, has begun to change. In the US and UK for example, #CripTheVote activists have campaigned to bring disability issues - such as the right to education - to the forefront. In India, there’s a web of legislation such as the Persons with Disabilities Act 2016 that broadly advocates for structural policy such as free education till the age of 18 years in integrated schools or special.schools and learning materials, development of appropriate learning environments and teacher training etc. The National Policy for Persons with Disabilities from 2006 also supports such overarching guidelines, along with central government schemes for education for people with disabilities.

Still, education for people with visual impairments - and opportunities for learning Braille - are still limited in scope. As of 2016, only 8.5% of American visually impaired students are identified as Braille readers. Braille illiteracy contributes to high unemployment rates for blind and visually impaired people, estimated to be 75 percent in Europe (according to the European Blind Union) and 70 percent in the United States, according to Cornell University’s Disability Statistics. These numbers are even higher on a global scale.

This can be at least partly attributed to the lack of specific policy on designing classrooms and educational initiatives aimed at empowering visually impaired children to learn about the evolving world in ways that allow them to take charge of their education and lives. In India, for example,the specifics of legislation related to inclusive and special education is left to lower federal levels such as the State, and their implementation at even lower levels such as the district. This means there is little coherence in educational approaches for the visually impaired.

Another major barrier in India’s case is limited opportunities for Braille education because parents and families of blind children - who may not have had access to good educational opportunities, or steady income themselves - often are unable to realize the value of educating their child. Even when in school, children may not receive sufficient training because very few teachers are themselves trained to teach Braille. Poorer regions of the country tend to have both a disproportionately high number of blind people and so fewer resources for educating them.

These challenges arise from circumstances of the people with disabilities, and a pattern of choices on the part of decision-makers. These choices can be different, better. Through a set of changes to how we think about and address Braille literacy, there are ways forward.

Paths to Better Braille Literacy

In recent years, there has been a push to ‘center’ people - be they learners in educational settings, users of products, or citizens with disabilities of a country - in designing and developing what they need to get the most out of their interactions with the world around them. To ensure Braille literacy is widespread and effectively reaches the people who would benefit from it the most, then, requires centering visually impaired children in how we develop the paths to Braille literacy.

What are the considerations for such learner- and disability-centred education? Most importantly, it’s that no fixed approach would be enough. Especially in children’s developmental phases, variable and person-centred approaches can go a long way in helping various students adapt to the needs of the classroom through means that help them leverage their individual strengths. The Learner-Centered Psychological Principles (or LCPs) offer a framework for these approaches. These include attention to individual developmental differences, appreciation of what the student is most interested in studying while setting appropriate challenges, teaching analytical and comprehension-based higher order thinking skills, and - among the most important for children with disabilities - creating positive interpersonal relationships with their peers and teachers. Inclusion is a value and a belief system that is rooted in concrete action.

Key to inclusive learner-centred education is the role of the teacher in the classroom. Those trained in the needs of children with disabilities can help the child navigate educational systems that weren’t necessarily built for them. Teachers used to teaching sighted children can also evolve their instructional strategies in partnership with both disabled students themselves as well as family and other instructors who have previously taught them and are specifically attuned to the child’s disability. In such forms of education, collaborative learning often becomes an important feature of classrooms, giving the teacher time to coach individual students and groups per their differences in learning methods. Students also have time to act as coaches for each other, allowing them to learn from each other and fill their gaps in knowledge, find new social groups to interact with, and try different modes of pacing and (self-)assessment.

Specifically for learners in and of Braille, the visual nature of most classrooms means that there must be an active shift towards a mix of text and audio tools to record and understand what is being taught in the classroom. For example, while some teachers may not mandate note-taking for visually impaired children, assuming they would lag behind their sighted peers, encouraging this practice means that these children assume their own strategies in recording and analysing the education imparted to them in a script that matches their preferences, i,e., in Braille. Ensuring that curricula are designed around including texts that are available in Braille, as well as texts that discuss Braille and represent the points of view of people with visual impairments.

In a case study noting the importance of guided literacy initiatives, Ilda Carreiro King notes that:

The...special needs student would take home an audiotape of his text-book and follow along as he listened. Because research has found that listening to books on tape does not improve comprehension unless the student is subsequently asked to read the text aloud to someone who can give feedback, the teacher in-corporated paired reading with coaching into her class….In addition, an expanding vocabulary and knowledge of a topic gained initially from reading books at his level generally helped him access more and more difficult books on the topic, swelling his pride in his accomplishments and feelings of being a true contributing member of the class. The teacher found that these techniques enriched learning for all members of the class.

It’s with teachers and their peers, then, that visually impaired children become part of a classroom that fosters an inclusive culture - from belief to norms to practice. Through collaboration, such classrooms provide seamless delivery of appropriate services to every student. By examining the cultural and ethical factors that encourage what is considered by the learner as inclusive practice, communities of learning can be more vibrant and thriving in difference.

Outside the educational sphere, however, there are still political and policy factors that are essential in laying the paths to Braille literacy. Policy-making can help address challenges, such as by standardizing approaches to Braille in blind schools across the country, accelerated by cheaper production and technological tools. Elevating Braille’s place in education will lend coherence to addressing illiteracy among the visually impaired, as a common point of beginning to address wider challenges. For example, with Bharati Braille that includes several major Indian languages, children can be taught to read and write in their own vernacular languages, providing a means to understanding the world in the languages they hear spoken around them. Braille can also improve citizens with visual impairments to participate in political processes, such as with the introduction of ballot papers in Braille.

The mission, at the end of the day, is for a comprehensive education to reach as many visually impaired children as possible through a variety of strategies. Increasingly, these strategies can also be through technological means - like with education for sighted children, there are new ways for visually impaired children to learn too.

EdTech’s Role in Braille Education

Braille education has remained more or less unchanged for decades. This has largely been due to the assumption that Braille is its own (analogue) medium, one that’s separate from digital and electronic technologies that are largely assistive - not instructive. But it’s not a good idea to treat such tech as either superseding Braille or ignoring their benefits for Braille use itself. Educational technologies that make use of such advances, without sacrificing the particular strengths of Braille, are one example of how technological innovation can complement Braille learning.

One of the key ways Braille learning can be updated is through bringing in multimodality. By utilizing the dynamic potential of combining hardware and software in increasingly portable forms, the tactile script of Braille can be supported by oral instructions that can be recorded and replayed to guide students. This also means education can be interactive without the need for constant human intervention - through educational games and intuitive feedback made possible on the same device, learners can learn from and correct their mistakes on the fly. Self-paced and self-directed learning, that allows students to adopt learning styles that they’re comfortable with, can also be made easily accessible through digitally stored learning materials that can be recalled anytime across hardware. For educators too, this means stepping away from micromanaging a student’s learning journey, and being able to take a wider view of their classrooms and focusing on the pedagogical and social elements of their teaching.

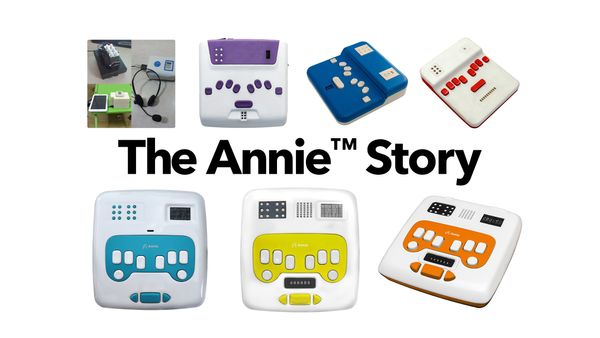

We’ve long recognized the strengths of technology in making Braille learning a more accessible and exciting experience - it’s what inspired our development of Annie, the world’s first Braille self-learning innovation. By presenting interactive and gamified learning materials that take advantage of the language-neutral form of the Braille script, we’ve been able to reach hundreds of students across the world with the companionable Annie guiding their education. Alongside a learner-centered approach to lesson pacing and ample opportunities to practice their Braille skills, Annie also provides a learning ecosystem that situates them in their classrooms and broader world. Excited kids talking about the games they play and the stories they’re made a part of have shown us that this is a way for students to talk to each other about what they’ve learnt in a natural and friendly way.

A Broad View on Braille Literacy

When it comes to how we can vastly improve the metrics of Braille literacy, we’re optimists at Thinkerbell Labs. We believe that its challenges are surmountable, and we have an array of tools, pedagogies, and technologies at our disposal to help. Still, we recognise that it is a long process, one that requires widespread and often structural changes. We hope to contribute to that by collaborating with schools, governments and most importantly, the children and educators themselves. The drops can add up to an ocean - one that quenches the thirst for knowledge that so many children with visual impairments have.

Find out how you can use Annie to tackle the issue of Braille illiteracy